AI, Accessibility, and the Risk of Easy Answers: Why Human Oversight Still Matters

When looking at accessibility solutions, AI automations tempt institutions with the holy grail of “fast, good, and cheap”; but as the business paradigm goes, you can't have all three—and accessibility is no exception.

The promise of faster workflows and fewer barriers is exciting, but efficiency can’t replace responsibility. And the irony of excluding humans from accessibility work is not lost. In the face of compliance and regulatory changes, fewer resources, and increased accountability, cutting corners with automated AI might seem practical in the moment, but it can expose institutions to risk and leave some students out in the proverbial cold.

The Temptation of “Easy” and Why It Doesn’t Deliver

At Anthology, we have embraced AI in ways that can support some tasks in teaching and learning but continue to underscore a simple truth: the work of teaching can be supported by AI, but can’t be handed over to it. The same is true of accessibility.

Again, the idea of one-click accessibility powered by AI is certainly appealing: click a button, check the compliance box, and move on. But that mindset risks trading true inclusive course content for superficial convenience and treats accessibility as an administrative task rather than a foundational part of teaching excellence. We believe accessibility has to be part of the design process, and if digital materials aren’t truly accessible, the work isn’t truly finished.

When institutions lean too heavily on automation, three common issues emerge: increased barriers for students, an over-reliance on technology, and a false sense of compliance, each of which we’ll detail below.

1. Increased Barriers for Students

In a recent article published by UNESCO, Alice Bennett from the Digital Accessibility Unit at the University of York noted that cutting humans out of the accessibility process can often introduce barriers for students while still seemingly “checking the box” when it comes to compliance. Using AI-generated alt-text, the essential descriptive layer that blind and low vision users rely on to make visual content meaningful, as an example, she wrote:

“Even when AI can correctly identify the subject of an image, it cannot identify the message you wanted to convey—a disadvantage, for example, to blind people or those who have limited vision. The auto-generated text can provide a starting point, a description you can edit as needed. But defaulting without checking or editing a generated description doesn’t necessarily fulfill the objective of image description. Unhelpful, incomplete, or inaccurate image descriptions do not provide equivalent access and could even create confusion or misinformation for anyone relying on this to fully engage with the content. The mere presence of an alternative text might make your content appear accessible, but unless it is meaningful, it is merely an illusion of inclusivity.”

In addition to what Bennet describes above, AI-generated alt text often includes much more detail than is necessary or relevant. Without human oversight and review, automated alt-text can be needlessly complex and burdensome for learners who are relying on it to convey meaning and context.

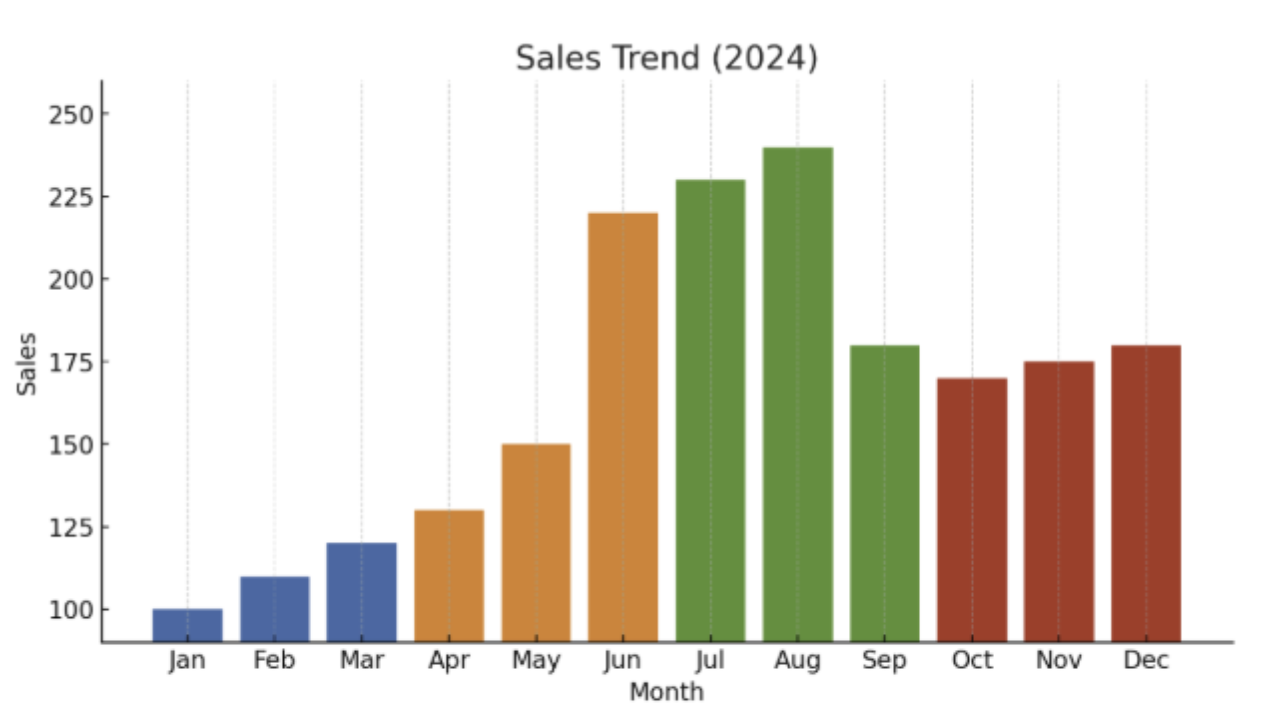

For illustrative purposes, below is an image of a sales chart used in a learning module about how seasonality can impact sales, followed by two versions of alt text—one written entirely by AI without any human correction, and one written by a person:

AI-generated alt text: A bar chart titled “Sales Trend (2024)” showing monthly sales from January to December. Each quarter is represented by a different color: blue for Q1, orange for Q2, green for Q3, and red for Q4. Sales start relatively low in January at around 100 and rise gradually through spring. A noticeable jump occurs in June, July, and August, which are the highest points on the chart, peaking in mid-summer. Sales then decline in September and remain moderately steady through the fall months.

Human-written alt text: A bar chart showing sales in 2024, with peak sales in the summer months of June, July, and August.

In addition to this powerful (and somewhat exhausting) example, AI fixes can also introduce additional errors such as the incorrect reading order of documents, make color-contrast changes that impact the meaning or purpose of a chart or visual aid, and add auto-generated captions for videos that can miss important context cues for students. And sadly, it’s the students who most depend on accurate, thoughtful accessibility features who are most impacted by these AI-powered tools that are supposed to be helping them.

2. Overreliance on Technology

When faculty are encouraged to “just click the button,” the long-term effect is more than incomplete remediation—it’s dependency. Tools that promise automated fixes after the fact don’t help instructors understand why the issue existed in the first place or how to avoid recreating it moving forward. And without that foundational knowledge, inaccessible design becomes a repeating pattern, and the institution becomes reliant on technology to continually patch the same problems over and over again.

This isn’t simply a workflow concern; it affects teaching practice. When instructors don’t develop fluency in essential accessibility skills such as writing meaningful alternative text, structuring documents with headings, and checking color contrast before building materials, they lose the ability to design content that reflects the needs of all learners. Over time, technology becomes the default decision-maker, and faculty are less equipped to recognize when automation gets something wrong.

The result is a cycle in which technology addresses yesterday’s issues while unintentionally creating tomorrow’s. Automated tools become perpetual band-aids rather than a path toward sustainable, accessible content creation.

3. A False Sense of Compliance

Again, we know the allure of “check-the-box” compliance is undeniable. In an environment where institutions face tightening budgets, rising accountability expectations, and new legal requirements under Title II, tools that promise to automate accessibility fixes can give leaders the impression that risk has been neutralized; that if the platform says content is “accessible,” the institution must be in the clear. But this just isn’t true.

AI-driven compliance often masks deeper issues. As noted earlier, AI-generated alt text may produce technically valid metadata while still misrepresenting the image. Auto-tagged PDFs may pass a machine check but still confuse blind students who rely on screen readers. Automatic video captions may meet a bare-minimum compliance threshold while omitting essential context because the instructor never actually read them.

From a compliance standpoint, this creates a dangerous disconnect. Institutions may feel protected because their accessibility tool reports a green checkmark, but students with disabilities actually experience something very different. And when a complaint or lawsuit arises, it’s the lived experience of the student, not the green checkmark, that will be scrutinized.

Leaders may believe that adopting AI tools demonstrates a good-faith effort to comply with accessibility regulations, but relying solely on automated fixes can be interpreted as neglecting meaningful accessibility practices. AI can support compliance; it cannot stand in for it (nor should compliance be the goal, but that’s a topic for another blog). Without human review and intentional design, institutions risk discovering too late that what felt “good enough” on paper does not hold up in practice when it directly impacts their students.

The Goal Isn’t “Easy.” It’s Sustainability.

The real conversation around AI, automation, and accessibility shouldn’t hinge on what is easiest—it should focus on how AI can support efficiency, sustainability, and building institutional capacity.

Anthology’s 2025 faculty survey and subsequent white paper highlights where faculty still struggle with accessibility:

- 29% of faculty say they lack awareness of accessibility best practices

- 27% say they haven’t received adequate training

But when accessibility becomes part of everyday workflows, supported by training, clear expectations, and the right tools that guide vs. automate, institutions see better and more sustainable outcomes. AI can streamline tasks, but people must continue to guide decisions and be the ultimate authors of course content that supports every student.

To that end, Anthology® Ally uses AI and automation to lighten the administrative workload; but, in alignment with Anthology’s Trustworthy AI framework, it never removes educators from the loop. Our approach centers on:

- Purpose-driven adoption of AI where it makes sense

- Pairing AI with human oversight, with every use of AI reviewed and approved before becoming student facing

- Measuring progress over time

This people-first model ensures AI strengthens expertise and supports inclusive design best practices rather than diluting them or worse, replacing them entirely. For example, Ally can provide AI-generated alt-text as a starting point for instructors as they’re building courses, but they’re required to review and approve the text, along with any edits as needed, before it becomes student facing.

Looking Ahead: Culture, Collaboration, and Continuous Improvement (Even After the Title II Deadline)

Accessibility is never a one-time project. It’s a cultural commitment. And while AI can reduce workload and expand capacity, it can’t replace the human judgment and creativity that make learning environments truly inclusive. If institutions try to meet the April 2026 deadline of Title II compliance by solely relying on AI, many will fail to deliver on the ultimate goal of making course content inclusive for all students of all abilities. However, if they treat it as the impetus to build a thoughtful accessibility program and bring on tools that educate instead of automate, they’ll meet the moment and set themselves up for what comes beyond the deadline.

Discover how Anthology Ally can become a meaningful part of your accessibility program and request a demo. You’ll see how technology can both educate and remediate, providing a scalable and sustainable approach to digital accessibility at your institution.